"No Kill" Was Hijacked by Puppy Killers. Here’s How to Restore Its True Meaning.

The term was co-opted by big money non-profits and “shelters” run by people who wield the needle without hesitation or remorse.

The Scoop New York is a newsletter dedicated to companion animals and the New Yorkers who care for them, from Buffalo to Brooklyn. NYC ACC KILLS, published by TSNY, enumerates and memorializes adoptable cats and dogs who were nonetheless exterminated by Animal Care Centers of New York City.

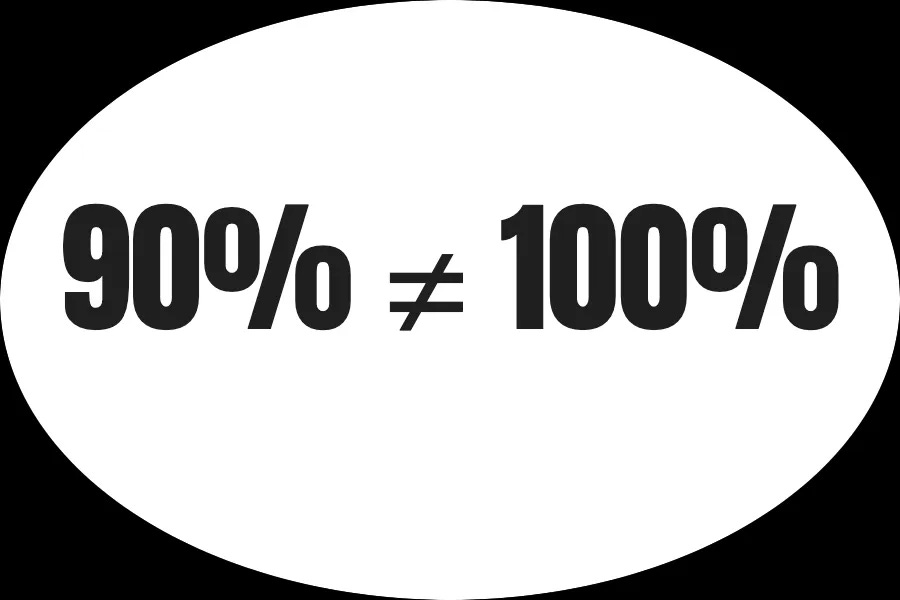

Late last year The New Yorker published a piece by writer Jonathan Franzen. It was called “How the No-Kill Movement Betrays Its Name,” and it was not what its title suggested.

Franzen is known, in no particular order, as a fiction writer, avid birder, and recidivist schmuck. He once considered adopting an Iraqi war orphan because he doesn’t understand young people. Worse than that, he shared those thoughts with the rest of us.

The New Yorker is known for vigorous, if not ruthless, fact-checking. That’s laudable, of course, especially given the present societal moment. Without parsing the details, let’s say that in this case The New Yorker either didn’t do much follow-up or they gave Franzen a free han…